LEARN MORE ABOUT

MAKING THINGS IN GLOBAL ASIA

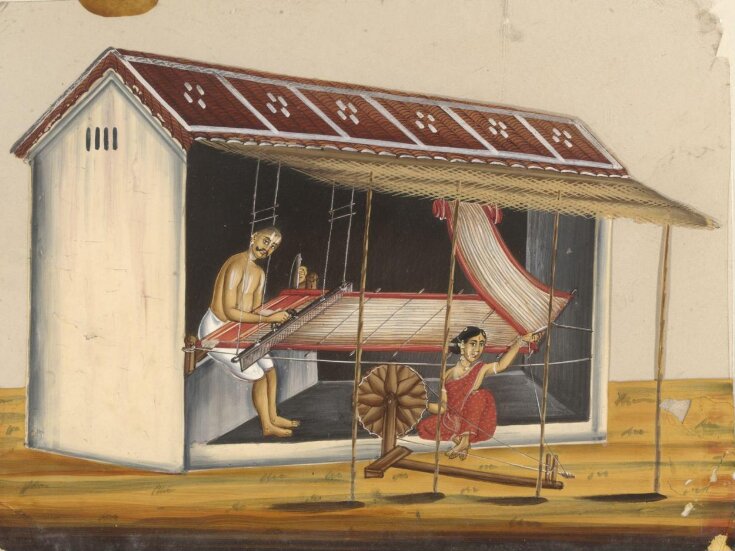

Long before Asia became the epicentre of global manufacturing at the end of the twentieth century, it was home to sophisticated cultures of production in the early modern period (1500-1800). This rich history has been obscured by narratives that see the Industrial Revolution of the period 1780-1830 as a domestic story of British (or at best, European) ingenuity. This exhibition, Making Things in Early Modern Asia, puts Asia centre stage. Early modern Asia was the world’s economic nexus, responsible for two-thirds of manufacturing. Commodities produced in early modern Asia transformed the consumption patterns of people worldwide, including in West Africa and the Americas. And this intercontinental demand for Asian commodities generated a truly global form of capitalism.

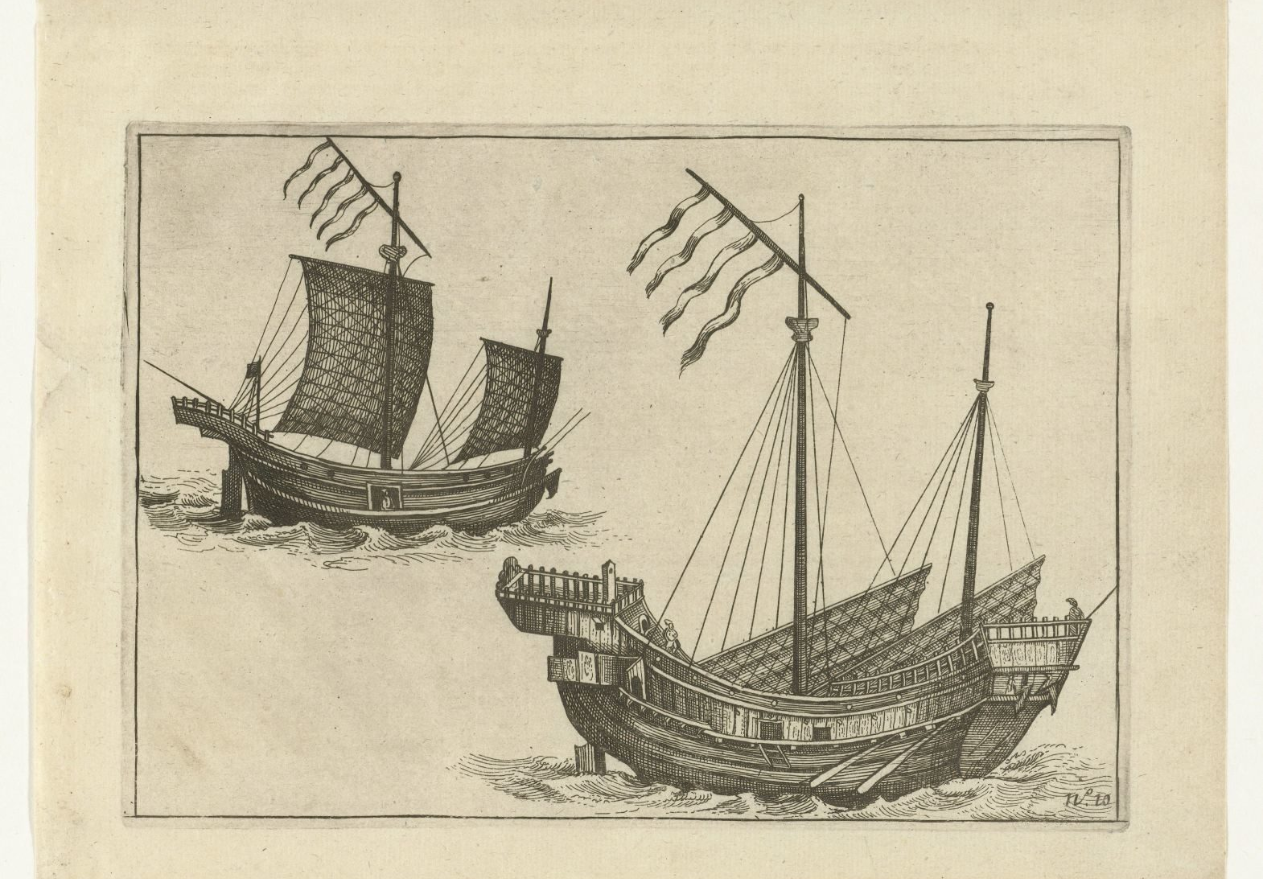

Two Chinese junks on their way to Canton (1607), anonymous, 1644 - 1646, from: Cornelis Matelief de Jong, Historisch Verhael Vande treffelijcke Reyse, gedaen naer de Oost-Indien ende China, met elf Schepen (Amsterdam 1644-1646), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

https://id.rijksmuseum.nl/200489176

Making things has been a concept intrinsic to how we think about capitalism ever since Adam Smith wrote of the division of labour in a pin factory in his Wealth of Nations (1776). But Smith described a world in which production was becoming heavily standardised. By contrast, things were made in fantastically diverse ways in early modern Asia. This exhibition takes a closer look at the varieties of production in Early Modern Asia through imagery.

It is organised into five themes: ecology, households, knowledge and technology, intermediaries, and imitation. Through a series of ‘sections’ dedicated to each of these factors, Making Things in Early Modern Asia highlights the overlooked, but nonetheless worldmaking, role of Asian manufacturing in the global history of early modern capitalism. Making Things in Early Modern Asia was created by CAPASIA, a project funded by the European Research Council and based at the European University Institute in Florence in collaboration with digital historian and web developer Antonello Mori. We furthermore thank Associazione Isole for their role in the development of the exhibition.