Mobilities

Introduction

For millennia, the Indian Ocean has been a hub for medium- and long-distance trade. Vessels of different types and sizes have sailed its seas and rivers, transporting people, goods, and intangible assets. Trade also flourished on the vast landmass surrounding the ocean, often requiring alternative modes of transport for long distances. This room explores some of the means that facilitated mobility across Asia.

Depiction of a kuroshio ocean current

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:North_Pacific_Currents-Kuroshio-nl.svg

The Kuroshio, or Black tide, is one of the most important ocean currents in East Asia. However, pre-modern travellers of the region were not so familiar with it, as their ships mainly operated within the epicontinental sea. Without the knowledge of this current, the maritime connection between the two continents bordering the Pacific Ocean was seriously hampered. In 1565, more than four decades after Magellan’s voyage, an expedition led by Miguel López de Legazpi and Andrés Urdaneta was able to map this sea current, founding a new trade route between America and Asia, known as “Manila Galleon”.

Ships

Folding Screen with the Arrival of a Portuguese Ship in a Namban screen, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam,

http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.2448

Since pre-modern times, shipbuilding and navigation were well developed in the coastal regions of the Indian Ocean. Different types and sizes of vessels were built, serving different purposes. Unlike overseas trade, which was carried out by a limited number of large ships like the one depicted in the image, coastal trade tended to be carried out by a large number of smaller vessels.

Riverborne traffic

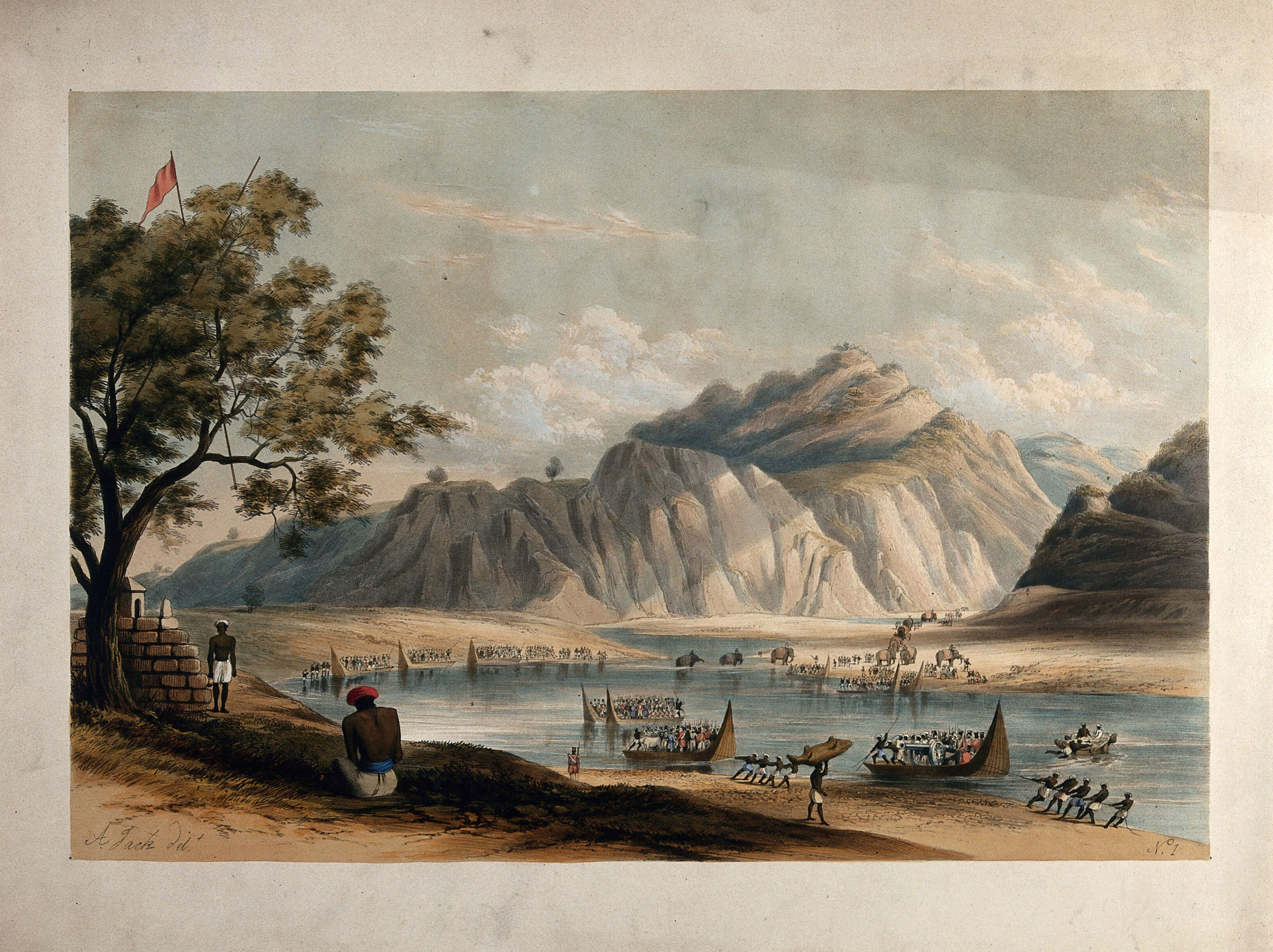

“Crossing the River Beas”, Himachal Pradesh. Coloured lithograph after Alexander Jack, c. 1847. Wellcome Collection,

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/rrwp4hae

Coastal and overland trade in India facilitated high-seas trade but also served other important economic needs. The infrastructure was region-specific, depending on the natural conditions. Northern India relied heavily on fluvial means, thanks to the great arteries of the Ganges and Indus Rivers providing an important channel for trade. In turn, Southern India’s inland waterways remained limited, with the greatest importance being in the western coastal strip.

Pack-bullock

A man driving a bullock cart laden with sacks. Watercolour by an Indian artist. Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/t8sy3mau

Because few rivers were suitable for transporting goods in Southern India, a great proportion of the peninsula’s overland trade was done in oxen, headloads, and porters. On Malabar, the bulk of the pepper that was neither consumed locally nor taken to the nearby ports was carried on asses and pack cattle to Comorin and returned with rice. In the sixteenth century, the overland routes in the region were revived due to the Portuguese attempts to monopolise the pepper trade.

Porters

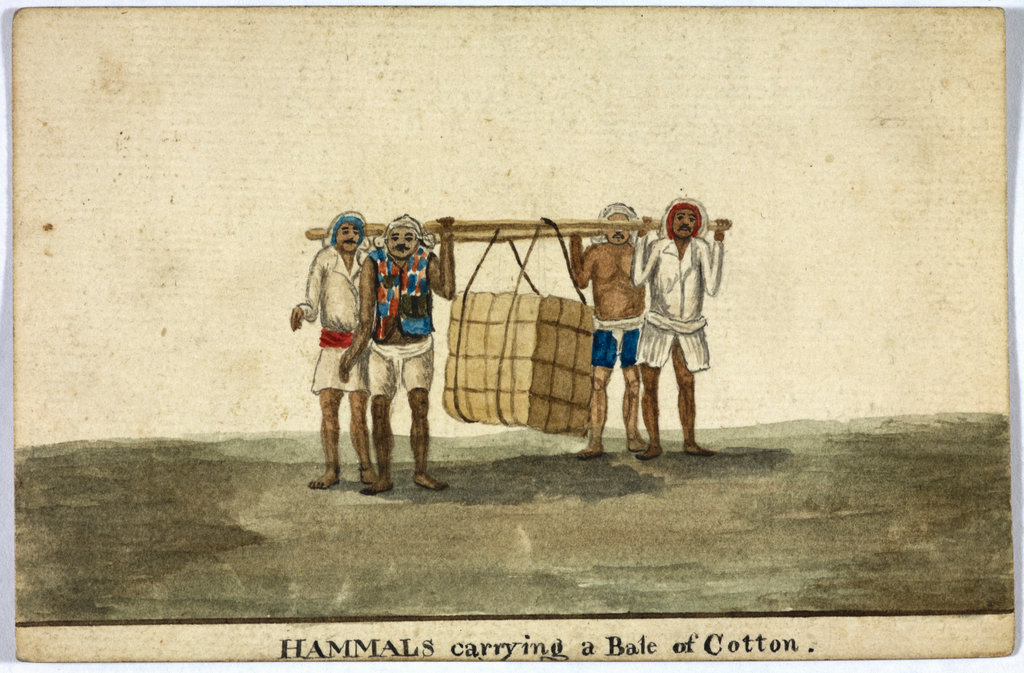

Title of Work: Bombay Views and Costume, 1810-11, British Library, London (Shelfmark: WD 315), https://imagesonline.bl.uk/asset/32766

In many places, the mountainous terrain rendered riverborne traffic impossible. Where the roads were too rough, people had to carry the goods. They could carry it individually – as a headload – or in groups, like the men in the image carrying a bale of cotton.

Warship

A sea battle between Japanese pirates and the Chinese, 1700-1800, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.64749

Trade and violence for much of human history developed side by side. However, in the early modern age, sea insecurity was aggravated by improvements in naval gunnery. Additionally, violence could spread more easily because European navigation brought previously separate maritime trading zones into contact.