Households

Introduction

Households were the main units of production and consumption in early modern Asia. They varied greatly over time and space, but everywhere households were reservoirs of human capital, skill, and innovation. They were also frequently sites of coercion and unfreedom, especially for women. Disparate customs, rules of inheritance, and conceptions of work shaped them in disparate ways.

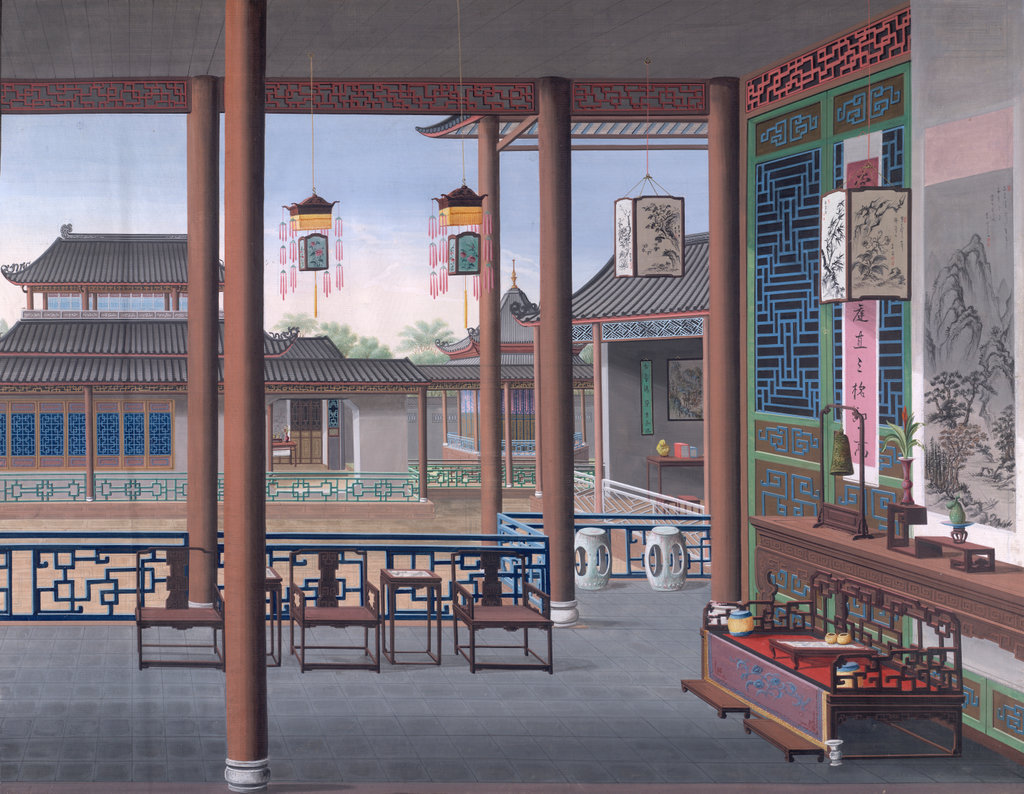

“House of a Chinese Official,” c. 1800-1805, Courtesy British Library, Add.Or.2191,

https://imagesonline.bl.uk/asset/16891

Household Composition

Far from being static, the composition of households often changed. Concubines, widows, children, and in-laws moved in and out of households. Frequently, the mechanisms of the market shaped these kinship structures. For example, stem families emerged in Japan to better adapt the household to the demands of the market. In India widow remarriage in certain areas was spurred on by the labour needs of households. Enslavement was also widely practiced among elite families.

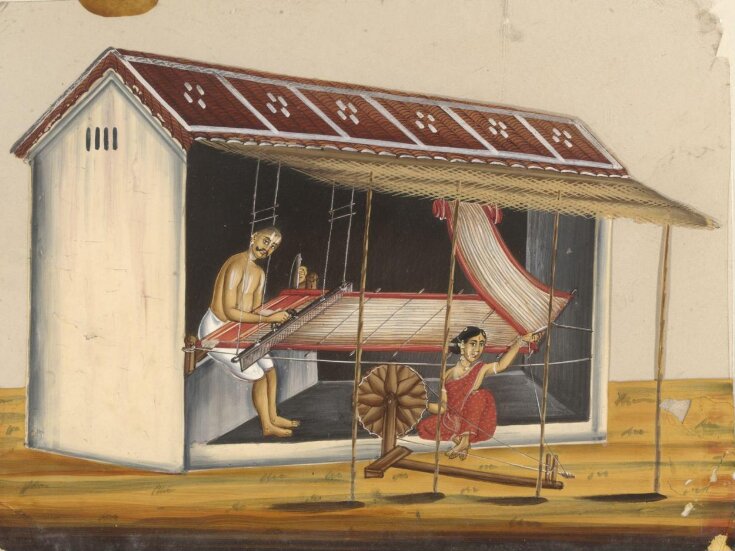

Agglomerations

In certain parts of Asia where the demands of production nurtured sophisticated divisions of labour there occurred agglomerations of households around particular industries. A consequence of this was the construction of production clusters at the sub-regional level. This was perhaps most visible in southern India, where numerous villages existed in which the majority of the population were engaged primarily in textile production, rather than in trade or agriculture.

Woman

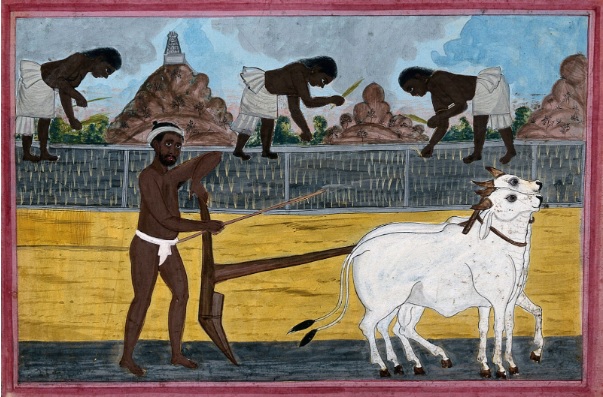

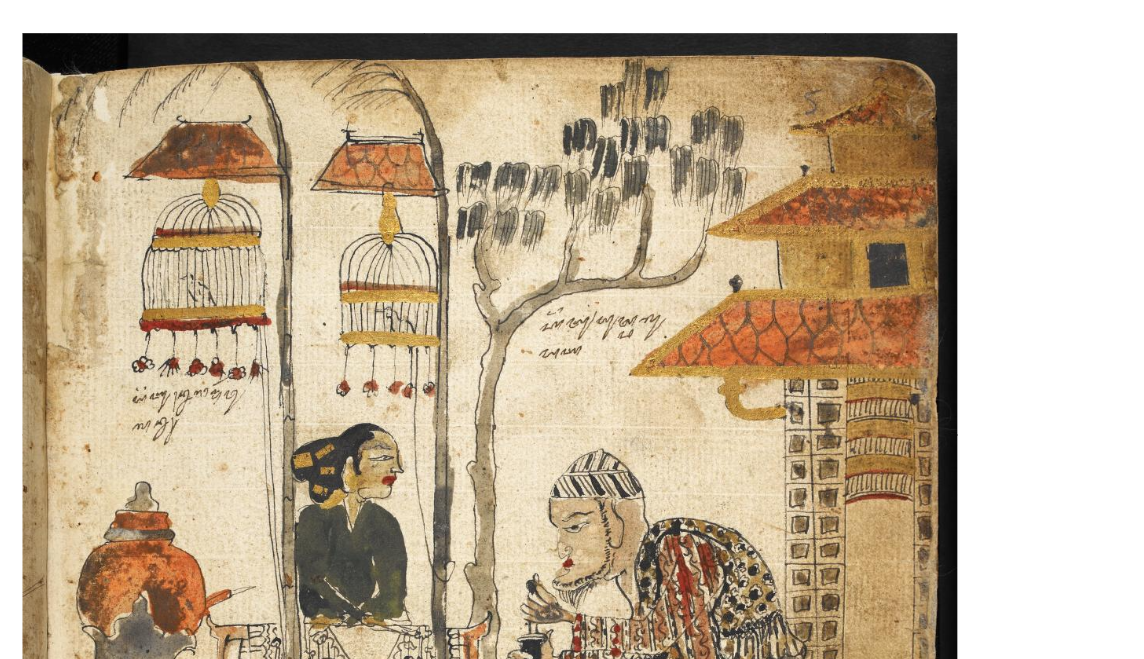

Households often produced and consumed for themselves. But almost no household was self-sufficient. Individual households altered their patterns of production depending on the season. In places like South India and Java many households were involved in both agricultural cultivation and textile production. Women shouldered the burden of production within the household, but their labour often remains invisible in the historical records. Unfortunately, only passing remarks give a sense of the scale of women’s role in production. In some cases, particularly in parts of Southeast Asia, women traveled outside the households as merchants to sell the commodities they produced at home.